Deep Sea Fish and Sediment Surveys in the Gulf

Oceanic Updates

Meet C-IMAGE Environmental Forensics Scientist: Erin Pulster

Aug 20th

Science is all about asking the right questions…and then carefully developing approaches that provide clear answers. The advent of new technology allows scientists to provide answers to particular questions with better and better resolution. In a nutshell, that is what the Environmental Laboratory for Forensics (ELF) at Mote Marine Laboratory does.

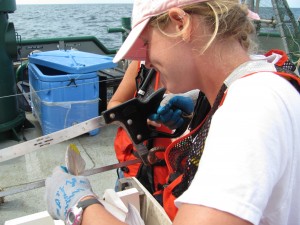

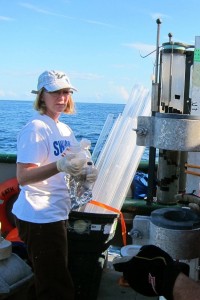

The fishes sampled during the C-IMAGE cruises are being analyzed biochemically by scientists at Mote Marine Laboratories in Sarasota, Florida. Scientist Erin Pulster is tirelessly processing tissue samples from over 300 fishes collected during this expedition. When a fish arrives on board, Erin swiftly draws a blood sample before the blood begins to coagulate. Then tissue samples from several organs are collected for later analysis at Mote Marine ELFS lab on shore. Each organ is being evaluated for possible DNA damage, while the blood is analyzed for fertility hormones and immune functions.

Erin works both on deck when fishes are collected and in the onboard lab. In the lab she carefully homogenizes (pulverizes) the organ tissues so the cells are isolated for preservation. The samples are frozen in liquid nitrogen, also called cryogenic preservation… now that sounds like forensics.

The ELF program was created by a team of scientists to use novel biomarkers to help answer pressing questions about effects of contaminants and other stressors. Biomarkers are specific physical or chemical responses that can be used to measure or indicate the effects on an organism due to some sort of stressor.

When used in conjunction with more traditional approaches, the careful and well-validated use of biomarkers can provide powerful insights…as is occurring through ELF’s efforts with snapper and other bony fishes, as well as sharks and even invertebrates exposed to oil in the Gulf disaster. ELF scientists are now using their unusual approach to better inform conservation efforts in a number of locations around the world.

The truth of the matter is that it is difficult to tease out all the environmental and human-related variables that could impact individuals and populations in the wild. The answers come slowly and with much effort, and scientists simply do not know at this point whether the Deepwater Horizon event could have impacted organisms exposed to the oil.

Meet C-IMAGE Graduate Students

Aug 19th

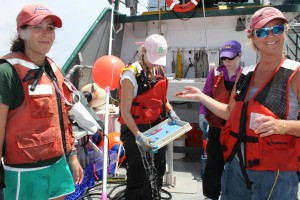

During our current expedition three new USF graduate students are participating, Liz Herdter, Jacquelin Hipes and Susan Snyder. Enjoy meeting these C-IMAGE graduate students who are working with C-IMAGE Chief Scientist, Steve Murawski. It is truly an exceptional opportunity to begin the first week of graduate school sailing aboard the Weatherbird II as part of the August cruises. For two students, this is their first time on a research cruise. This C-IMAGE cruise is These ladies, aka ‘the fish ladies’ have been immersed during the longline bottom fishing. These students have tirelessly processing the demersal fishes– snapper, tilefish, grouper, eels and sharks collected at depths of 100 to over 1000 meters. The processing includes making standard and fork length measurements, weighing the fish, and removing blood and tissue samples.

Susan Snyder: Master’s Student, USF College of Marine Science (Advisor- Steve Murawski)

I got my BS in Biology and a minor in Chemistry from the State University of New York at Geneseo. During my undergraduate research I studied symbiotic cyanobacteria living within clonal sea star larvae collected from the gulf stream and also the macrophyte communities in Conesus Lake. I am now starting my Master’s degree with a concentration in Marine Resource Assessment at USF College of Marine Science working with Dr. Steve Murawski. This cruise on the Weatherbird has been my first experience as a new student at USF. It’s been a lot of hard work and long days but I am having so much fun! It’s great to be out in the ocean with a team of scientists so dedicated and enthusiastic about their work! I am very much looking forward to starting classes and my new life in St Pete!

Liz Herdter: Master’s Student, USF College of Marine Science (Advisor- Steve Murawski)

I got my BS in Biology at Boston University. During the past seven months I have been working in Dr. Steve Murawski’s lab as a research technician. I have been on several longline cruises this summer. However, this August C-IMAGE cruise is my first time aboard the Weatherbird II. This Fall I am starting my Master’s degree with a concentration in Marine Resource Assessment at USF College of Marine Science and will continue my work with Dr. Murawski. This cruise aboard the Weatherbird II has been fun and very rewarding.

Jacquelin Hipes: Master’s Student, USF College of Marine Science (Advisor- Steve Murawski)

I’m just starting the first year of my MS in Biological Oceanography at USF CMS. I graduated from Louisiana State University in May 2012 with a BS in Biological Sciences and a concentration in marine biology (Geaux Tigers!). I was born and raised in Dallas, TX, but that didn’t stop me from being fascinated with marine science from a very young age. (I’d also like to take up a little space to say “Howdy” to my parents, Jackie and Mark, and brothers, Chris and Austin, back home- love y’all!)

Jacquelin Hipes (USF-marine science graduate student) with shark sampled as part of C-IMAGE August cruise

The reason I’m so excited to be working with Steve at USF is that I can finally branch away from the invertebrate work I did in my undergraduate years and study sharks! I’m on the first leg of the Weatherbird II cruise right now to help Steve longline for benthic fishes and collect samples of organs, tissue, and otoliths (ear bones) for analysis at the College’s lab in St. Petersburg. Our lab group is particularly interested in if any of these animals have been negatively impacted by the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Since I’ve just started, I don’t have my own project yet but I definitely have some good ideas to consider, now that I’ve spent almost a week on a research vessel!

Profile of the crew of the Weatherbird II

Aug 19th

The Florida Institute of Oceanography operates two vessels that are utilized by member institutions and the wider marine science community to further scientific research on the Gulf of Mexico, its ecology, marine life and sustainability.

Captain Matt White

Captain Matt began his ventures at sea in the Coast Guard, where he started as a seaman, and worked his way up the ranks during his 12 year career. He majored in Liberal Arts. He has been with the Weatherbird II for 3 1/2 years. Growing up in the city, until the Coast Guard, never had a calling for water. When not out at sea, Matt spends time with his wife and two year old daughter.He also enjoys home remodeling and computers.

When asked about his favorite expedition memory, Matt responded, ” This is a hard question, over the course of sixty plus cruises, the scientists have made great discoveries: finding a subsurface oil plume, 250m below the surface, rare sharks and critters brought up from 1000+ meters. I am truly lucky to be a part of such great discoveries, that will last a lifetime.”

Ryan Healy; Assistant Captain

A Bachelor’s degree in Geography from Frostburg State in Maryland set Ryan on his path out to sea. He has 13 years of experience on various vessels, but considers his true introduction to sailing occurred at the age of six. Ryan started on the Weatherbird II on February 14, 2012.

Ryan has done a lot of long distance tall ship sailing, the kind ships which resemble pirate ships. In fact, he worked on the very ship used on the making of the movie, “Master and Commander”. When not cruising professionally, Ryan enjoys sailing as a hobby and traveling. His favorite experience was sailing cargo across the South Pacific, when two islander fishermen were aboard. They routinely played their ukuleles which they came to believe attracted the fish. Ryan, when off watch, would lie in his hammock, listening to their music. When asked if he believed the music attracted fish, he said, “I don’t know but if they didn’t play, they didn’t catch fish.”

George Guthro; Assistant Engineer

This is the ninth year of sailing aboard Florida Institute of Oceanography vessels for George. He has been on the Weatherbird II for three years. Between serving in the Navy and spending 35 years as a professional truck driver, George has been just about everywhere, including throughout the Caribbean, Hawaii, Australia, Japan and the Philippines. His work aboard the Weatherbird II , leaves little time for anything else.

Chris Baily; Assistant Engineer

Chris began his nautical career in the U.S. Coast Guard, where he worked for several years. He has also ventured into the business world as a restaurant manager. For the past thirteen years, Chris has been on vessels full time, the last year and a half on the Weatherbird II.

Chris considers his best life experience to be having his two sons, Tristn, age 13 and Ayden, age 8. When not aboard the Weatherbird II, he spends time at the gym, the beach and of course, more fishing! Getting to experience seeing all of the islands in the Caribbean while in the Coast Guard is one of his most memorable experiences.

Andrew Warren – Science Technician

Andrew earned his B.S. in Geographic Information Systems from Florida State and a B.A. in Environmental Science from U.S.F. His six years of vessel experience includes working for the Center of Ocean Technology and 1 ½ years aboard the Weatherbird II .

Andrew’s life experiences include diving on the Great Barrier Reef at age 16. He now spends his off time fishing, diving, kayaking and anything else outdoors.

His favorite memorable experience is snow-skiing for the first time in Grindelwald, Switzerland six years ago.

Andrew, the communications technician, handling the communication instruments, tracking weather and monitoring the data from the CTD (conductivity, temperature and depth recording device).

Mike Moles; Weatherbird II chef Mike attended Ohio State and Columbus State, majoring in Hospitality Management. He has been cooking up delicious meals aboard vessels since 1986, and only joined the Weatherbird II a month ago, but has graciously provided us with scrumptious meals all week long. When not cruising, he likes to work out at the gym and make his own beer.

Mike’s most memorable venture at sea was a 21 day cruise across the Atlantic to Italy in the roughest weather he has ever experienced, up to 20 foot seas.

The Man Behind the C-IMAGE Fish Catch

Aug 19th

Willy Stephens; Professional Fisherman hired by C-IMAGE

Willy has been fishing all of his life, learning from his father and grandfather. After attending Marianna High School in Marianna, Florida, Willy began his 20 year career as a professional fisherman. He was hired by Dr. Steve Murawski to work aboard the Weatherbird II because of his immense skill at finding the fish while keeping everyone safe. He is truly a professional, conscientious, hard-worker who is appreciated for his efforts.

When not working, he enjoys his two children, Haley, 12 and Trevor, 11. And guess what he does for fun. Yes, he goes fishing! For Willy, “Fishing is Life”.

When asked what his favorite experience at sea has been, he responded, “when I caught 18,000 POUNDS OF Red Grouper in a week.”

Meet C-IMAGE Scientist: David Hastings

Aug 18th

Dr. David Hastings is a marine chemist and Professor at Eckerd College. Enjoy Hastings photo story as he shares his science contribution to the C-IMAGE project.

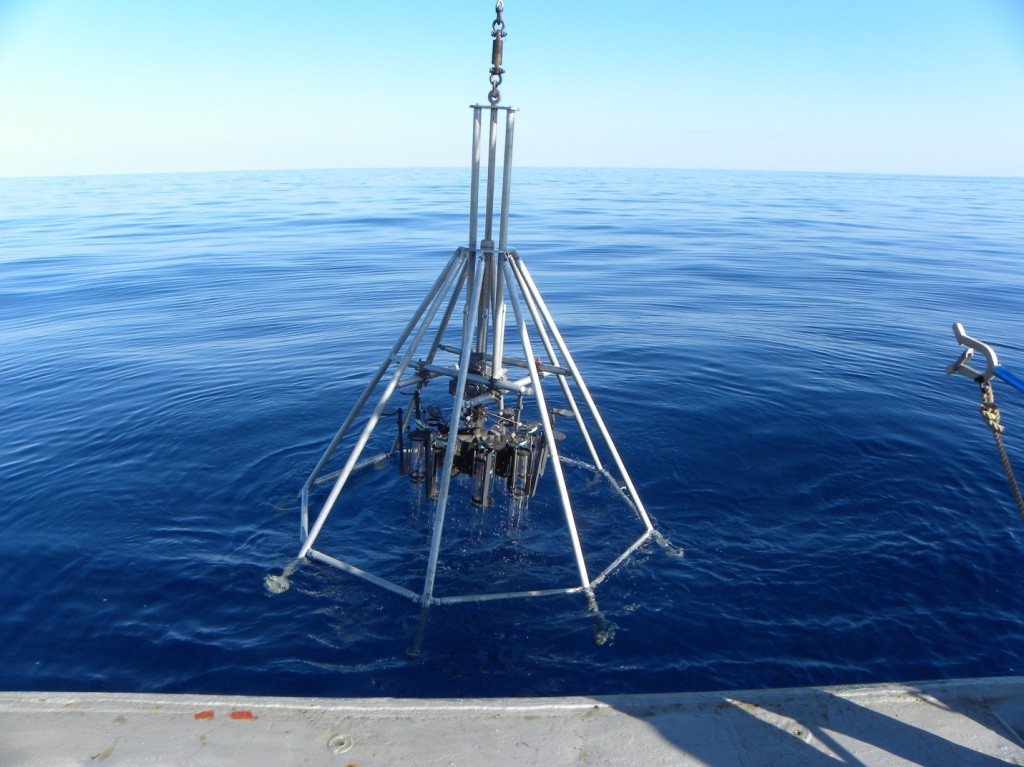

Following the oil spill, we are very interested in both the fate and transport of the oil. Where did it go? We think that some of it went into the ocean sediments, and we want to know the eventual demise of the oil. We collect sediments (aka mud) from the ocean bottom in order to try and answer these questions using an instrument called a multi-corer. Note that there are 8 separate core barrels since there are many different scientists who want the samples.

We first need to transfer the sediment from one core liner to another. We store the sediment for many analyses that are done later back in the lab on shore.

Even though there is no light in ocean sediments at the depths we are sampling, there is still some life at the ocean floor. What do you think these organisms are?

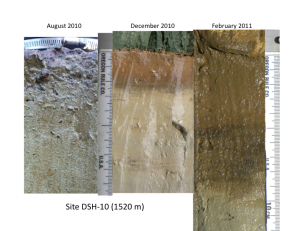

After the oil spill, there was a large pulse of sedimentation from the surface waters that has a different coloration from the sediments beneath. The rate of sedimentation following the oil spill is 100 times greater than before!

The water in the sediments is important to fully understand the chemical processes involved in the decomposition of oil and other organics. Here I am using a set of syringes to suck water out of the mud for later analysis. I am eager to find out the results of this experiment!

Meet C-IMAGE Scientist: Patrick Schwing

Aug 18th

Dr. Patrick Schwing is working after graduation as a Postdoctoral scientist for the C-IMAGE project at USF’s College of Marine Science. Enjoy the following Photo Story of his science research and activities during the C-IMAGE August 2012 cruises.

This is a picture that was taken aboard the R/V bellows during one of our seafloor surveying cruises with Dr. Stan Locker in the Dry Tortugas National Park. We were using a C3D side-scan sonar instrument to obtain a high definition map of seafloor bathymetry. This was paired with airborn LIDAR maps to create a complete map of the National Park.

Following the Deepwater Horizon Blowout in 2010, several cruises went out to assess the impact on the seafloor. This is a picture of the MC800 multicorer that was used to obtain short sediment cores throughout the northeastern Gulf of Mexico. The multicore “lunar lander” is the perfect instrument for capturing the sediment-water interface and surface sediments. It also collects eight cores at once, allowing for several different analyses to be done at the same site with only one cast.

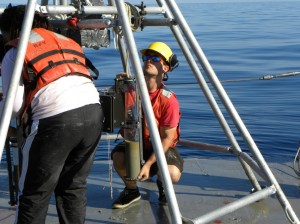

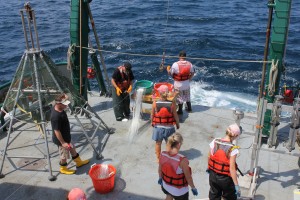

Once the multicore returns to the deck, the sediment tubes must be retrieved as shown below. The sediment is then transferred into other tubes that have been cut to size for each core. They are then sealed and kept at cold temperatures while they await sampling and analysis in the lab.

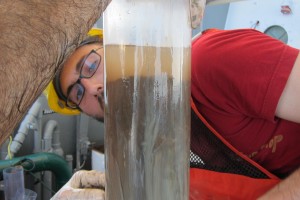

One of the cores is split longitudinally and cleaned for photography. The other seven cores are used for short-lived radioisotope dating, organic geochemistry, benthic foraminifera abundance and stable isotopes, microbial analysis, reduction/oxidation metal chemistry, pore water chemistry, and an archive core.

This series of photos was taken of three cores taken from the same site at different time intervals. It is evident that a large amount of material has been deposited between August 2010 and February 2011. The short lived radioisotope geochronology has shown that the mass accumulation rates have increased by one, and in some cases, two orders of magnitude. The increase in deposition is most likely due to settling of plankton due to hydrocarbon toxicity or blooms of microbes in the water column that thrived during the blowout.

The benthic foraminifera (single-celled carbonate protists) picked from each sample depth in the core were counted, photographed in case of deformation (photo on right), and analyzed for their carbon isotope composition as an indicator of direct contact with hydrocarbons. The foraminifera pictured here are Cibicidoides wuellerstorfi (“healthy” specimen in photo on left).

Why is the Dean of Marine Science on board the ship?

Aug 18th

You might wonder why a Dean would bother to go out on a cruise. As Dean, my role is more about “managing” science rather than “doing” science. It is difficult to find the time to participate in fieldwork. One of my faculty, Robert Weisberg, likes to say that “you can’t manage a system you don’t understand.” That applies equally to running an organization or managing an ecosystem like the Gulf of Mexico. With respect to managing the college, I can’t make wise decisions unless I have a firm working knowledge of what the students, staff, and faculty are experiencing. Though managed by the Florida Institute of Oceanography, cruises on our ships the R/V Weatherbird II and R/V Bellows are an important part of life for everyone at the College of Marine Science. It is useful for me to experience life aboard the vessels. With respect to the Gulf of Mexico, I was an active participant in the effort to get our C-IMAGE center funded, so it makes sense for me to participate in this cruise, as I certainly have “skin in the game”.

Being out here reminds me why I fell in love with this line of work in the first place – a community of people working together to solve important scientific questions that they are passionate about. You get to focus on what you love, without the distractions of day-to-day life. And it’s really nice to have someone do all the shopping and cooking for you!

What has been the most interesting part of the cruise for you?

Usually when I go to sea, I am either dredging for volcanic rocks or using a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) to collect rocks. When rocks come on deck, they don’t wriggle, thrash, squirm or bite. In particular, the sharks and king snake eels have been quite exciting! At least I’m not doing the dissections! That would be too much for any self-respecting geologist to do.

How did you get started in oceanography?

I didn’t plan to be an oceanographer, but I was prepared because I was taking basic science and math as an undergraduate, and I was willing to jump on an opportunity that became available. It helps to be at the right place at the right time, but you have to be able to recognize an opportunity and be willing to take it.

I first went out to sea when I was an undergraduate at Stanford University. It wasn’t a class or an organized undergraduate research experience. Instead, I was given an opportunity to volunteer on a research cruise to the central Pacific at the exact moment I had decided to take a break from school. I had no job, no place to live, and no clear plan for my major and someone offered me a two-month all-expenses paid trip (but no salary) to Hawaii and Panama. It didn’t take me long to say yes. During that cruise, I learned how to be a scientific navigator using transponder navigation. This was before the days of GPS. The excitement of “doing” science as part of a team, instead of memorizing information from a textbook, inspired me to change my major to geology once I returned to school in the fall. As I finished my bachelor’s degree, I went on to work at the US Geological Survey as a scientific navigator on their ship the R/V S.P. Lee. I was aboard the ship when hydrothermal vents were discovered on the Juan de Fuca Ridge in the NE Pacific. That was a career-defining event for me and I stayed on for a master’s degree in geology and studied the volcanic rocks erupted on the seafloor along the Juan de Fuca Ridge.

If you study volcanoes, what can you possibly contribute to the study of the Deepwater Horizon disaster?

The beauty of oceanography is its interdisciplinary nature. My specialty is the study of gases in magmas and volcanic rocks. Volcanic eruptions are driven by the expansion of gas that exsolves from magma as the pressure drops during ascent from depth to the surface. This is similar to what causes champagne to spew from the bottle when the cork is popped. It turns out that the basic physics of the deep well blowouts are very similar to those for explosive volcanic eruptions or hydrothermal vent plumes. They all involve rapid rise of a buoyant multi-phase plume that interacts with the medium through which it travels (seawater or atmosphere) and separates into different layers. I like to describe the blowout as an eruption of petroleum and gas on the seafloor. Some of the best estimates of the volume of oil spilled into the Gulf come from scientists at Woods Hole using technology developed to study hydrothermal vents at mid-ocean ridges. Our C-IMAGE center combines research on the physics of an evolving oil-gas-dispersant plume into different parts (what floats, what dissolves into seawater, what gets suspended, and what sinks to the bottom), how these parts evolve with time (physical and biological degradation), and how each part impacts the surface, shallow, and deep ecosystems.

C-IMAGE: The Lighter Side of Science Aboard WBII

Aug 18th

Susan Snyder (graduate student), David Levin (journalist) and Liz Herdter (graduate student) enjoying the ice cream always in supply

Tonight’s blog features some of the lighter side of life aboard a scientific research cruise. We hope you will enjoy this photo montage of the scientists, post doc, graduate students and teachers. We will continue the science stories in the next blog.

C-IMAGE voyage aboard Weatherbird II is a radio guy’s dream

Aug 17th

My job on this voyage is to help tell the story of C-IMAGE as it works to uncover the long-term environmental impact of the Deepwater Horizon spill. Over the course of the cruise, I’ve been wielding a microphone, conducting interviews on the fly, and collecting the sounds of the ship for a series of radio pieces that will be available on the C-IMAGE website in a few months. (The scientists, I should add, have been amazingly patient and gracious as I shove a mic in their face all day long).

The Weatherbird II is a radio guy’s dream: an environment full of rich sound. In the background is a constant hum of engines, the occasional clank of a winch, the thrashing of fish and sharks as they’re pulled aboard, and the visceral crack and pop of fish skulls as they’re split open by Steve Murawski’s team of biologists during dissection. When I’m not recording these sounds, I’m pitching in with fieldwork.

-

Collecting samples while at sea is hard work, and it takes every extra set of hands available. Since I’m more of a night owl than a morning person, I’ve pulled the graveyard shift, working with geochemist David Hollander, marine chemist David Hastings, and post-doc Patrick Schwing. The three spend the wee hours of each night taking sediment samples from the ocean floor with a device called a multi-corer. It’s a metal frame that looks a bit like a giant spider with a rack with eight plastic tubes hanging within it. As the device is lowered onto the bottom, those tubes sink into the mud and silt, then seal shut to trap the sediments.

The multicore tubes have been specially built to slice into the muck, and they need to be reused each time. To save each sample, the four of us need to transfer it to another thin plastic tube with a specially built extruder (essentially a rubber cap on top of a thin metal pole). Once it’s safely inside the new tubes, we wash the original tubes and set them back onto the multicore for its next trip to the bottom.

Transferring the cores is a wet, muddy job, but it comes with moments of complete wonder. Half of each tube is filled with silt, and the other half, seawater. At the threshold between the two is an intact piece of the ocean floor, exactly as it looked more than 3,000 feet below. Occasionally, it shows evidence of tiny worms or other burrowing creatures.

Hollander and his team aren’t after these animals—they’re interested in the chemistry of the sediments, and how toxins from the Deepwater Horizon spill may have leached into the silt. Staring into the samples we bring up, however,

I find myself fixated on that tiny slice of the sea floor. Stuck in its clear plastic tube, it seems like a relic from another planet.

In its own way, I suppose, it is. Although the bottom is less than a mile away, it’s a completely alien world—harsh, inaccessible, and uninviting. But these core tubes offer us a window into that world, and place it at our fingertips for a few moments on the deck of the ship.

I can’t wait to see what tonight brings.

Day 2: Catch of the day

Aug 15th

Patty’s Post: We woke up to the news that while we peacefully slept, the work continued, putting out 5 miles of long-line with a total of 500 hooks and the hope of finding what diversity of fish life resides at >1000 meters in the Gulf waters.

Notice the stomach extruding from the mouth due to the expansion of swim bladder as pressure decreases at the surface.

C-IMAGE Chief Scientist, Dr. Steve Murawski, a professor at USF College of Marine Science, has two new graduate students, just starting their master’s program. All are standing by eager to help with the fish catch. One of these students, Susan Snyder, just moved down from New York state the day before the cruise left. What a great way to start your first year at USF!

Some of the specimens caught today include smooth dogfish sharks, snappers, a Southern stingray (Dasyatis americana), yellowedge groupers and tilefish.

- As the fish are brought in, graduate students, technicians,scientists stand by, ready to process them. Processing includes weighing, measuring, drawing a blood sample, removing the gall bladder, a sample of bile, cutting off a piece of their liver, and removing the otoliths (ear bones) for further study.

How old is this fish? The earbones of fishes help to determine the age by counting growth rings deposited in the bone