Adventures at Sea

Deep Sea Fish and Sediment Surveys in the Gulf

Deep Sea Fish and Sediment Surveys in the Gulf

Feb 11th

The C-IMAGE project has scientists at many stages in their career. Meet three C-IMAGE research technicians who are vital to the at sea field and on shore lab research for C-IMAGE: Karen Dreger, Jonelle Basso and Matt Garrett. All have sailed many times aboard the C-IMAGE cruises which began in 2010. Enjoy their sea stories.

Karen Dreger, M.S., the SIPPER Captain

Karen Dreger, M.S., the SIPPER Captain

Karen Dreger is a Research Engineer Technologist at the University of South Florida. She operates and maintains the Shadowed Image Particle Profiling and Evaluation Recorder (SIPPER) instrument. SIPPER allows scientists to view zooplankton in their own environment and at scales that allow them to better understand how plankton interacts with each other and their surroundings. SIPPER also carries a suite of environmental sensors to monitor water quality parameters to better understand the environments in which the organisms live.

Karen has a diverse background in both the science and technology fields. In 2010 she earned a Masters degree in Environmental Science from USF. This is Karen’s 13th Oil Response cruise. She has spent over 90 days at sea traversing the Gulf of Mexico aboard research vessels.

C-IMAGE Jonelle Basso and DEEP-C Brian Wells collecting microbes from deepsea sediments collected from Shipek sediment grab during Feb C-IMAGE cruise

Jonelle Basso, M.S., Microbe Expert Jonelle Basso is a Marine Microbiology Laboratory Technician and a veteran sailor – this being her 9th trip to collect samples of marine microbes. Jonelle collects water samples from the Niskin Bottles and completes 2 types of tests on them. She runs a toxicity test using bioluminescent plankton and bacteria to measure how toxic the water is. The less light the little guys give off, the more toxic the water.

Her other test is a mutigenicity test. She introduces 2 strains of E. Coli into the water samples to see if they stimulate phage production. Both tests help her determine the health of the water. When not at sea Jonelle teaches and works in the Microbiolgy Lab of C-IMAGE scientist, John Paul; Use this link to visit the lab (http://www.marine.usf.edu/microbiology/)

Matt Flynn (Eckerd), Jonelle Basso (USF, center), Matt MacGregor (C-IMAGE teacher) filtering seawater for Carbon Hydrogen Nitrogen (CHN) concentrations to be determined at on shore lab

Feb 11th

Another great part of conducting science research at sea is meeting and working with a number of graduate and undergraduate students. This C-IMAGE cruise we have sailing with us, Elizabeth Brown and Bo Yang from USF College of Marine Science and Matt Flynn from Eckerd College. As well as, Brian Wells and Lee Russell from Florida State University as part of the DEEP-C consortia (see their blog entries). Enjoy these stories about the USF students aboard.

Elizabeth Brown, USF Graduate Student

Hi! I’m Elizabeth. I’m a paleontologist – I’m not the kind who studies dinosaurs (although I love dinosaurs), even if I always get asked that ^^;; I study marine microfossils; tiny creatures the size of a grain of sand, some of them only a single cell, called foraminifera, or “forams” for short. Forams are among the oldest creatures in the evolutionary record. The oldest we’ve found are over a billion years old, and the genus is still going strong today. That’s what makes them so critically important to people like me, who study how the ocean has changed over the ages! Larger, more famous fossil animals, like mastodons, dire wolves, megalodon sharks, pterodactyls , and triceratops are wonderful, but they lived for relatively short periods of time in the big picture of geologic history. It’s like judging a photo album by a single snapshot. Studying how the tiny forams lived & evolved for so long gives us a much broader idea of changing earth, glaciers and oceans.

You know that phrase “You are what you eat?” Well, turns out, that’s true! Forams build their bodies and skeletons, incorporating various nutrients and elements (calcium, magnesium, barium, carbon, oxygen, etc) directly out of the ambient seawater. Their fossil remains are therefore a snapshot of the ocean chemistry at the time the creature was still alive.

Elizabeth Brown and Karen Dreger successful retrieval of the SIPPER plankton imaging system during C-IMAGE cruise

What’s more, ocean chemistry changesin mathematically predictable ratios with major changes in the environment: major temperature changes, major shifts in salinity, global sea level vs. formation of huge glaciers on land, all kinds of things you’d never think you could see through a fossil plankton (woah!). In short, by breaking down fossil skeletons of tiny forams, analyzing their chemical proportions, and doing a little back-calculating, I can track the evolution of the oceans through the ice ages. How crazy is THAT!?

Bo Yang, USF Marine Science Graduate Student

Bo Yang is a third year graduate student at CMS in Dr. Byrne’s lab. He is working with a team of scientists conducting long term monitoring of the CO2 system in Gulf of Mexico, a research project sponsored by NOAA. His team measures four things in seawater–the pH, carbonate ion concentration, dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), and total alkalinity (TA). Two measurements must be measured on board because they are very sensitive to interactions with the atmosphere; these are pH and carbonate ion concentrations. Bo uses spectrophotometric methods to measure the pH and carbonate ion concentration soon after the seawater samples arrive onboard from the Niskin bottles. These methods are the most accurate in detecting very small changes in the ocean’s chemistry related to acidification. The dissolved inorganic carbon and total alkalinity are measured on shore on shore in the lab from the water samples collected while at sea.

Bo’s academic timeline

Bo’s name in Chinese means wave and he has spent many days at sea experiencing waves firsthand. For his research he has sailed 130 days at sea including cruises in the East and South China Sea, Gulf of Mexico, Western Atlantic, Northeast Pacific, and Bering Sea. Bo completed his Bachelor’s degree in Xiamen University in China in marine science with a major in marine chemistry and a Master’s degree in environmental chemistry to develop a new technique to measure pH using spectrophotometry. While in China he had read about Dr. Byrne’s research and decided to study abroad for his PhD with Dr. Robert Byrne’s. Visit Dr. Byrne’s at http://www.marine.usf.edu/faculty/robert-byrne.shtml

Why monitor CO2in the ocean?

For Bo’s research the issue is ocean acidification which is a decrease in the pH of seawater. This is a phenomena being observed throughout the global ocean system. Seawater is naturally well buffered with an average pH of 8.2. This constant pH level provides a stable environment for sea life however the chemistry of the ocean is changing so that pH levels are decreasing which causes the ocean to be more acidic. A little change in pH has big impacts on the ocean’s critters, especially those with carbonate shells or other external structures that protect the softer internal parts of the plants and animals. The ocean absorbs about a quarter of the CO2we release into the atmophere every year, so this is a benefit of the ocean absorbing this greenhouse gas. However, as atmospheric CO2 levels increase, so do the levels in the ocean. This is the downside of the CO2 absorbed by the ocean… it is changing the chemistry of the seawater, a process a process called ocean acidification. For some nice educational resources on Ocean Acidification visit NOAA at http://www.pmel.noaa.gov/co2/story/OA+Educational+Tools

Bo Yang in Long Lab while in transit to first sampling station awaiting first water samples C-IMAGE cruise

Feb 10th

Cedric Magen, Ph D

DEEP-C Post Doc

Cedric Magen is on board the Weatherbird II to collect water samples and conduct tests that can be utilized to further his research to help understand the distribution, role, and cause of methane in the oceans; specifically the Gulf of Mexico. Scientists have known for years that methane concentrations increase at about 50-100 m depths below the sea surface, in well oxygenated waters. However, methane is typically produced in anoxic environments. Scientists have investigated this paradox for a few decades now, but so far, have not been able to explain it. Methane is typically produced by methanogens, microbes in sediments. It will sometimes escape the sediment to the overlying waters , leading to high concentrations next to the sea floor. It can also be released from natural oil seeps, at the same time oil is released. These deep sources of methane cannot explain the methane peak at 50-100m, simply because methane coming from the sea floor is oxidized before it makes it to the sub-surface waters. Scientists have come up with several hypothesis for this peak (e.g., by-product of zooplankton metablolism, presence of anoxic micro-environments associated to marine particles where methanogens could grow, etc.), but have not yet been able to demonstrate these hypothesis in-situ.

Cedric has been busy collecting methane data that will be used in a model to try to correlate methane distribution with other parameters collected on board. As Cedric stated to C-IMAGE Teacher at Sea, Matt MacGregor, “What you see me doing now is the easy part. Now I have to go to the lab and try to come up with an explanation for the vertical distribution of methane in the Gulf”.

Feb 10th

Wm. Brian Wells, PhD student, Florida State University

I am a Biological Oceanographer and my current work is focused on determining the time needed for degradation of the oil spilled from the Deepwater Horizon accident by naturally occurring microorganisms. Degradation in this sense is the assimilation or removal of the oil from the environment. Microorganisms use oil for food and some prefer specific compounds of the oil over others.

I am a Biological Oceanographer and my current work is focused on determining the time needed for degradation of the oil spilled from the Deepwater Horizon accident by naturally occurring microorganisms. Degradation in this sense is the assimilation or removal of the oil from the environment. Microorganisms use oil for food and some prefer specific compounds of the oil over others.

We look at the various sediment settings and through experiments in the lab and at sea, we can estimate the impacts of future spills. This research cruise is the eighth cruise that I have taken sediment cores from shallow shelf sites and the deep sea. Some of the cores will have oil added to the sediments and we will monitor oxygen consumption and other parameters to quantify microbial respiration. We will also look at the carbon: nitrogen ratios of the sediments back at our lab.

Microbial samples will be sent to partner scientist to determine which organisms are responsive to inputs of oil. Cores are used by other scientists to do many different things and we will freeze cores taken on board and distribute to others. I am a native Floridian and have been interested in the ocean my entire life. I have been fortunate to have the opportunity to be a part of the Deep-C consortium through the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative. My ultimate goal is to do my part to ensure that future generations have the same opportunities to enjoy the Gulf of Mexico as much as I do.

Lee Russell, PhD student, Florida State University

My name is Lee Russell and I am currently working towards a PhD at Florida State University. I am a Biological Oceanographer and my main research focus revolves around bubbles. That’s right, bubbles. I came to be involved with this top secret bubble project in a sort of round-about way. After graduating high school, like many people, I had no clue what I wanted to do with my life or remotely what direction I wanted to send it in. Well, that’s not entirely true. I knew I had just been through 12 years of school and I knew I wanted to do some good for people. So I started my undergrad degree in Political Science. By the time senior year came around, I had taken enough classes dealing with environmental science that a double major was possible, so I decided to take a few more classes so that I could double major. With graduation closing in, still having no clue about a life direction, I took a class called “Current Environmental Issues”, taught by an FSU Oceanography professor and things changed. This was the first class that actually “made sense” to me in terms of being applicable to real life. Yes, I finally got inspired my senior year of college. Applying for graduate school at FSU Oceanography has been the most important and easiest decision I have made in my life.

So here I am on the RV Weatherbird II, pulling tubes of mud from the bottom of the sea floor and I couldn’t be happier. You may say “what in the world does that have to do with saving the environment, Lee?”, and you would be right to say that. But it’s not about that. It’s not about mud, bubbles or the manatees. It’s about the explosion of knowledge and the widened perspective I have gained in the past 2-3 years working towards my graduate degree. Maybe I would have come to know some of the things I know now, but not in this accelerated fashion. Graduate school has been my true education. I look forward to applying the knowledge I have gained of intricately minute and incredibly massive ecological systems in a way that creates real change, both politically and educationally. Enough of the esoteric stuff, I’ll get back to the business on the boat. I am here not for my own research, but to provide assistance for some fellow researchers.

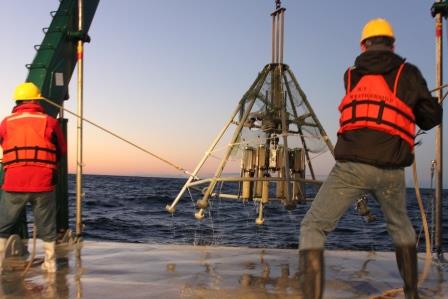

I have been mostly tasked with helping to get the 1000 lb multi-corer (they call it the lunar lander because that’s what it looks like) on and off the boat, which can get quite hairy when the seas are rolling like they have been this cruise. Once we get the sediment cores

on deck (sometimes they are mud, sometimes sand, depending on depth), we slice them up, bag the sections, and freeze them to save them for analysis when we get back to our lab at FSU in a week or so. I have also been tasked with pumping seawater from the surface of the cores through specialized filters. When we are back in the lab scientsits can tell if there are oil-degrading bacteria living in the water. Remember the oil spill?

Feb 10th

Lee Russell and Brian Wells (DEEP-C scientists) Deploying the Multicorer to Retrieve Sediment Samples

During this C-IMAGE expedition, the C-IMAGE team is collaborating to share vessel time with scientists from the DEEP-C consortia housed at Florida State University. Collaboration is an excellent way for scientists from multiple GoMRI consortia to work collectively to better understand the Gulf ecosystem. In the field of oceanography collaboration amongst science teams is essential to study large ocean systems. This is especially helpful when research is conducted at sea. We are enjoying learning about the research and sea stories of the DEEP-C scientists aboard. Enjoy this series of blogs that will introduce you to the FSU research team from the DEEP-C consortia, Brian Wells, Cedric Magen and Lee Russell.

Feb 10th

This has been a great cruise with the Captain and Crew keeping us safe, sound, and well fed.

The R/V Weatherbird II captain and crew include Brendon Baumeister “Boomer” (Captain), Ryan Healy (Assistant Captain), Mike Adams (Chief Engineer) (Photo Not Available), George Guthro (Assistant Engineer), Andrew Warren (Science Technician), Thomas Lee (Chef), and Chris Bailey (Deck boss).

Feb 10th

Enjoy a collection of photos of the scientists of the R/V Weatherbird II on the February 2013 Ocean Grazers Expedition.

Science Personnel include Leslie Schwierzke-Wade (USF) – chief scientist, Matt Garrett (USF/FWRI), Karen Dreger (USF), Jonelle Basso (USF), Bo Yang, Elizabeth Brown (USF), Brian Wells (FSU), Lee Russell (FSU), Cedric Magen (FSU), Teresa Greely (USF), Matt MacGregor (Teacher at Sea), and Matt Flynn (Eckerd).

Feb 10th

Enjoy a collection of photos of the scientists of the R/V Weatherbird II on the February 2013 Ocean Grazers Expedition.

Science Personnel include Leslie Schwierzke-Wade (USF) – chief scientist, Matt Garrett (USF/FWRI), Karen Dreger (USF), Jonelle Basso (USF), Bo Yang, Elizabeth Brown (USF), Brian Wells (FSU), Lee Russell (FSU), Cedric Magen (FSU), Teresa Greely (USF), Matt MacGregor (Teacher at Sea), and Matt Flynn (Eckerd).

Leslie Schwierzke-Wade is the Chief Scientist for the C-IMAGE expedition. She completed her masters degree at USF Marine Sciences and is now working for C-IMAGE scientist Kendra Daly to lead plankton monitoring research in the Gulf of Mexico.

Matt Garrett works for Florida Marine Research Institute (FWC-FMRI) and is a new graduate student at USF Marine Science with C-IMAGE scientist Kendra Daly's lab.

Feb 10th

February 9, 2013

Today began with a concerted effort by both the crew and science personnel of the Weatherbird II to deploy as much equipment and gather as much data as possible before an impending front arrived. As I mentioned previously, equipment cannot be deployed in rough seas. In fact, after having a conversation with some of the scientists on board, I discovered that a high percentage of ocean scientific missions are delayed in some way. Some never leave the dock, others are diverted to a safe port for a day or two or just wait at sea in a holding pattern until weather improves, or; in this case, the mission returns early. These decisions are based upon weather information available to the captain. Captain Boomer and Chief Scientist Leslie Schwierzke-Wade met, discussed the options, and acted accordingly. Decisions are based upon the safety of the vessel and everyone on board, the scientific equipment, and the ability to retrieve data. The danger component increases exponentially as the seas increase. I was told that on some of the research cruises, the Gulf of Mexico has been very calm and every station was easily covered. Right now we are carefully making our way safely back to port…….and it is rough!

Feb 10th

February 8, 2013

This morning began with the Northern most station, PCB01, right off Panama City. This was a shallow site at only 25 meters depth. We arrived on site at 0600. At one point land could be seen until the fog rolled in. We were even able to get cell phone connection! Now, we’re heading back along the transect line collecting data using the SIPPER and stopping at every predetermined station to collect data. We had visitors along the way.